Your basket is currently empty!

Few dates in history resonate with the same profound impact as October 14, 1066. On this autumn day, amidst the rolling hills near what is now the town of Battle in East Sussex, England, two titanic forces collided in an encounter that would forever alter the course of English history and reverberate across the European continent. The Battle of Hastings wasn’t just a clash of armies; it was a crucible in which modern England began to take shape, a testament to ambition, resilience, and the brutal realities of medieval warfare.

The Protagonists: A Throne in Dispute

To truly grasp the significance of Hastings, we must first understand the tangled web of succession that preceded it. At the heart of the conflict lay the vacant throne of England, left empty by the death of the childless King Edward the Confessor in January 1066. Edward, who had spent much of his youth in exile in Normandy, had a complex relationship with its ambitious duke, William. William claimed that Edward had promised him the English throne, a claim bolstered by a supposed oath sworn by Harold Godwinson, the powerful Earl of Wessex, during a visit to Normandy years earlier.

Harold, however, was a formidable figure in his own right. The most powerful nobleman in England, he had effectively governed the country for years under Edward. Upon Edward’s death, Harold was elected king by the Witenagemot, the Anglo-Saxon council of wise men, and crowned. This act immediately set him on a collision course with William, who viewed Harold as a usurper and vowed to claim his “rightful” inheritance by force.

Adding another layer of complexity was Harald Hardrada, the fearsome King of Norway, who also laid claim to the English throne, backed by Harold’s estranged brother, Tostig Godwinson. This triple threat set the stage for one of the most dramatic years in English history.

The Long March: A King’s Ordeal

Before facing William at Hastings, King Harold was forced to contend with Harald Hardrada and Tostig’s invasion in the north. In a stunning display of military prowess and speed, Harold marched his Fyrd (part-time soldiers) and Housecarls (professional bodyguards) over 185 miles in just four days, catching the invaders completely by surprise. The ensuing Battle of Stamford Bridge on September 25, 1066, was a crushing victory for Harold, annihilating the Norwegian forces and killing both Hardrada and Tostig.

However, this triumph came at a heavy cost. Harold’s army was exhausted, depleted, and far from home. It was precisely at this moment, just days after Stamford Bridge, that news reached Harold: William had landed his massive invasion fleet at Pevensey Bay in Sussex on September 28. There was no time to rest, no time to regroup. Harold had to turn his weary army around and force-march them south, covering another 250 miles in less than three weeks to confront the Norman threat. This incredible feat of endurance, though ultimately futile, speaks volumes about Harold’s leadership and the loyalty he commanded.

The Field of Battle: Senlac Hill

By October 13, Harold’s army, though weary, had taken up a strong defensive position on Senlac Hill (now known as Battle Hill), a ridge offering a commanding view and a natural advantage against the advancing Normans. The Anglo-Saxons formed their famous shield wall – a dense, interlocking formation of shields that presented an almost impenetrable barrier to cavalry charges. Their primary weapons were the fearsome two-handed Danish axes, capable of cleaving a man and his horse in two.

William’s army, in contrast, was a tripartite force: heavily armored knights on horseback, archers and crossbowmen, and infantry. Their strategy relied on coordinated attacks, with archers softening the enemy before cavalry charges attempted to break their lines.

The Clash: A Day of Blood and Deception

The battle commenced on the morning of October 14. For hours, the Norman archers rained down arrows, but the Anglo-Saxon shield wall held firm. William’s cavalry charges repeatedly crashed against the English lines, only to be repelled by the disciplined Anglo-Saxon defenders and their deadly axes. The Norman losses mounted, and at several points, their lines wavered, seemingly on the verge of collapse. Rumors even spread that William himself had been killed, forcing him to ride through his ranks, helmet aloft, to reassure his men.

It was then that William employed a cunning, though perhaps initially accidental, tactic: the feigned retreat. Norman cavalry would pretend to flee, drawing segments of the Anglo-Saxon shield wall to break ranks and pursue them down the hill. Once separated from the main formation, these eager Anglo-Saxons would then be cut down by the Norman cavalry turning to face them. While initially a desperate maneuver, William recognized its effectiveness and used it repeatedly. Each time, a small breach was created in the shield wall, exploited by the Norman knights.

As the day wore on, the Anglo-Saxon shield wall, though still formidable, slowly began to thin. The constant pressure, the exhaustion, and the devastating “feigned retreats” took their toll.

The Fall of Harold: The Turning Point

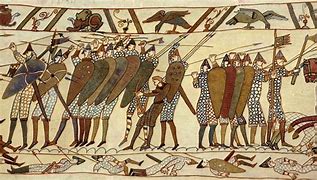

The precise moment of King Harold’s death remains a subject of historical debate. The famous depiction on the Bayeux Tapestry shows an arrow striking him in the eye, followed by Norman knights cutting him down. Regardless of the exact circumstances, Harold’s demise was the decisive moment. With their king fallen, the Anglo-Saxon resistance crumbled. The battle ended in a rout, with the remaining English forces fleeing into the night.

The Aftermath: A New Era Begins

William’s victory at Hastings was total and catastrophic for Anglo-Saxon England. On Christmas Day, 1066, he was crowned King William I of England in Westminster Abbey, earning him the moniker “William the Conqueror.”

The Norman Conquest ushered in a period of profound transformation. French became the language of the court, law, and administration, profoundly influencing the development of the English language we speak today. A new feudal system was imposed, replacing the existing Anglo-Saxon social structures, with Norman lords replacing the English aristocracy. Grand Norman castles sprang up across the land, symbolizing the new power structure. The Domesday Book, commissioned by William, was an unprecedented survey of land and resources, cementing his control over his new kingdom.

The Battle of Hastings was more than just a battle; it was the birth of a new England. It brought England firmly into the mainstream of European feudalism, linking it culturally and politically with France and the Continent for centuries to come. The legacy of 1066 is etched into the very fabric of English identity, a reminder of a pivotal day when one of history’s most audacious gambles paid off, forging a nation in the crucible of war.