Your basket is currently empty!

In the vast tapestry of human conflict, where battles often rage for days, weeks, or even years, one particular engagement stands out for its astonishing brevity. On the morning of August 27, 1896, off the coast of Zanzibar, the British Empire engaged the Sultanate of Zanzibar in what would become known as the Anglo-Zanzibar War. From the first shell fired to the hoisting of the white flag, the conflict lasted a mere 38 minutes, cementing its place in the history books as the shortest war ever recorded. Yet, behind this almost comically brief encounter lies a complex web of imperial ambition, strategic maneuvering, and a dramatic succession crisis that illuminates the raw power dynamics of the late 19th century. To truly understand why a global superpower would launch a full naval bombardment on a small island nation for less than an hour, we must delve into the intricate history of Zanzibar itself and the relentless “Scramble for Africa.”

Zanzibar: The Jewel of the Indian Ocean and a Prize of Empire

Long before European powers cast their covetous gaze upon its shores, Zanzibar held an unparalleled position as the premier trading hub of East Africa. Its strategic location, nestled off the coast of what is now Tanzania, made it a natural crossroads for trade winds and maritime routes stretching from Arabia and Persia to India and the Far East. For centuries, dhows laden with spices, ivory, gold, and, tragically, enslaved people, plied its waters, making Zanzibar a vibrant, cosmopolitan melting pot of cultures and commerce.

This prosperity attracted the attention of the Omani Sultanate, a powerful maritime empire based in Muscat. In the early 19th century, Sultan Said bin Sultan, a visionary and ambitious ruler, made the pivotal decision to relocate his capital from Oman to Zanzibar in 1832. Under his astute leadership, the Sultanate flourished, solidifying its control over vast swathes of the East African coastline, including Mombasa, Dar es Salaam, and the lucrative caravan routes into the interior. Zanzibar City, with its bustling Stone Town, became an economic powerhouse, fueled largely by the notorious but immensely profitable slave trade, alongside cloves and ivory.

However, the late 19th century ushered in a new era of global competition: the “Scramble for Africa.” European colonial powers – primarily Britain, Germany, and France – aggressively sought to carve up the African continent, driven by industrial needs for raw materials, new markets, and strategic geopolitical advantage. Zanzibar, with its deep natural harbor, abundant resources, and pivotal location, became a highly coveted prize.

Britain, already a dominant naval power with vast interests in India and the Suez Canal, saw Zanzibar as critical to safeguarding its trade routes and projecting influence in the Indian Ocean. Concurrently, Britain was increasingly vocal in its opposition to the slave trade, a moral stance that also served as a convenient pretext for intervention and expansion in regions where slavery was rampant. German interests also began to assert themselves, with Germany establishing claims to significant territories on the East African mainland adjacent to Zanzibar.

The Anglo-German rivalry over East Africa intensified, threatening to erupt into direct conflict. To avert this, the two powers negotiated the pivotal Anglo-German Treaty of 1890, often referred to as the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty. Under the terms of this agreement, Germany formally relinquished all claims to Zanzibar in exchange for the island of Heligoland in the North Sea (a small but strategically important naval base) and recognition of German territorial claims in mainland East Africa (Tanganyika). Critically, this treaty formally recognized Zanzibar as a British Protectorate.

This designation meant that while the Sultan nominally retained his internal authority, Britain effectively controlled Zanzibar’s foreign policy and defense. A key, though often unspoken, stipulation of the Protectorate was Britain’s right to approve the appointment of future Sultans. This right was crucial for ensuring a compliant ruler who would uphold British interests, particularly the suppression of the slave trade and the maintenance of Zanzibar as a stable coaling station for the Royal Navy. For Britain, Zanzibar was not just a trading post; it was a vital lynchpin in their global imperial network.

The Spark: A Sudden Death and a Usurper’s Ambition

The precarious balance of power in Zanzibar, carefully orchestrated by the British, was suddenly shattered in August 1896. For six years, the island had been governed by Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, a relatively pro-British ruler who had ascended to the throne with London’s full backing. His reign was characterized by a gradual integration of British advice into the Sultanate’s administration, moving towards the eventual abolition of the slave trade and modernization efforts.

However, on the morning of August 25, 1896, Sultan Hamad died suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of 39. While the official cause of death was pneumonia, immediate suspicions of poisoning circulated, particularly given the circumstances that followed. Many pointed fingers at his ambitious and less compliant nephew, Khalid bin Barghash. Khalid was no stranger to the inner workings of the Sultanate; he was the son of a previous Sultan, Barghash bin Said, and had long harbored his own aspirations for the throne. Unlike Hamad, Khalid held strong anti-British sentiments and resented the growing encroachment of British influence over Zanzibar’s affairs. He believed that the Sultanate should retain its full sovereignty and resisted the gradual dismantling of the traditional, slave-based economy.

Seizing the moment of chaos and uncertainty following Hamad’s death, Khalid acted with remarkable speed and audacity. Within hours of his uncle’s demise, and crucially, without seeking or receiving the mandatory British approval, Khalid bin Barghash marched into the palace and declared himself Sultan. He swiftly consolidated his position, ordering his loyal palace guards and a significant number of armed civilians to fortify the palace complex. Barricades were erected, and rudimentary defenses were prepared, reflecting Khalid’s determination to resist any British attempt to remove him. He also had at his disposal the Sultan’s armed yacht, the H.H.S. Glasgow, a former royal yacht converted into a makeshift warship, equipped with some cannons and machine guns, anchored strategically in the harbor.

The news of Sultan Hamad’s death and Khalid’s unilateral usurpation reached the British authorities in Zanzibar almost immediately. Sir Arthur Hardinge, the senior British diplomat and Consul General in Zanzibar, and Rear Admiral Harry Rawson, the commander of the British naval squadron stationed in the region, were the primary figures on the ground. For Hardinge and Rawson, Khalid’s actions represented a direct challenge to British authority and a blatant violation of the terms of the Protectorate. Allowing Khalid to remain on the throne without British consent would set a dangerous precedent, undermining the very foundation of their control over Zanzibar and potentially inspiring similar defiance across other British protectorates.

The British response was immediate and unequivocal. Hardinge dispatched a clear message to Khalid, demanding that he stand down and vacate the palace, reiterating Britain’s exclusive right to approve the new Sultan. The British had already identified their preferred candidate: Hamoud bin Mohammed, a more pliable and pro-British member of the Al Busaid dynasty, who they believed would cooperate fully with their agenda, especially the abolition of the slave trade. Khalid, however, remained defiant. He reportedly believed that he could garner support from other European powers, particularly Germany, whose consulate was located nearby, or that the British would not resort to military action. This belief was either a profound miscalculation or based on a desperate hope for external intervention that never materialized.

The Ultimatum and the Gathering Storm

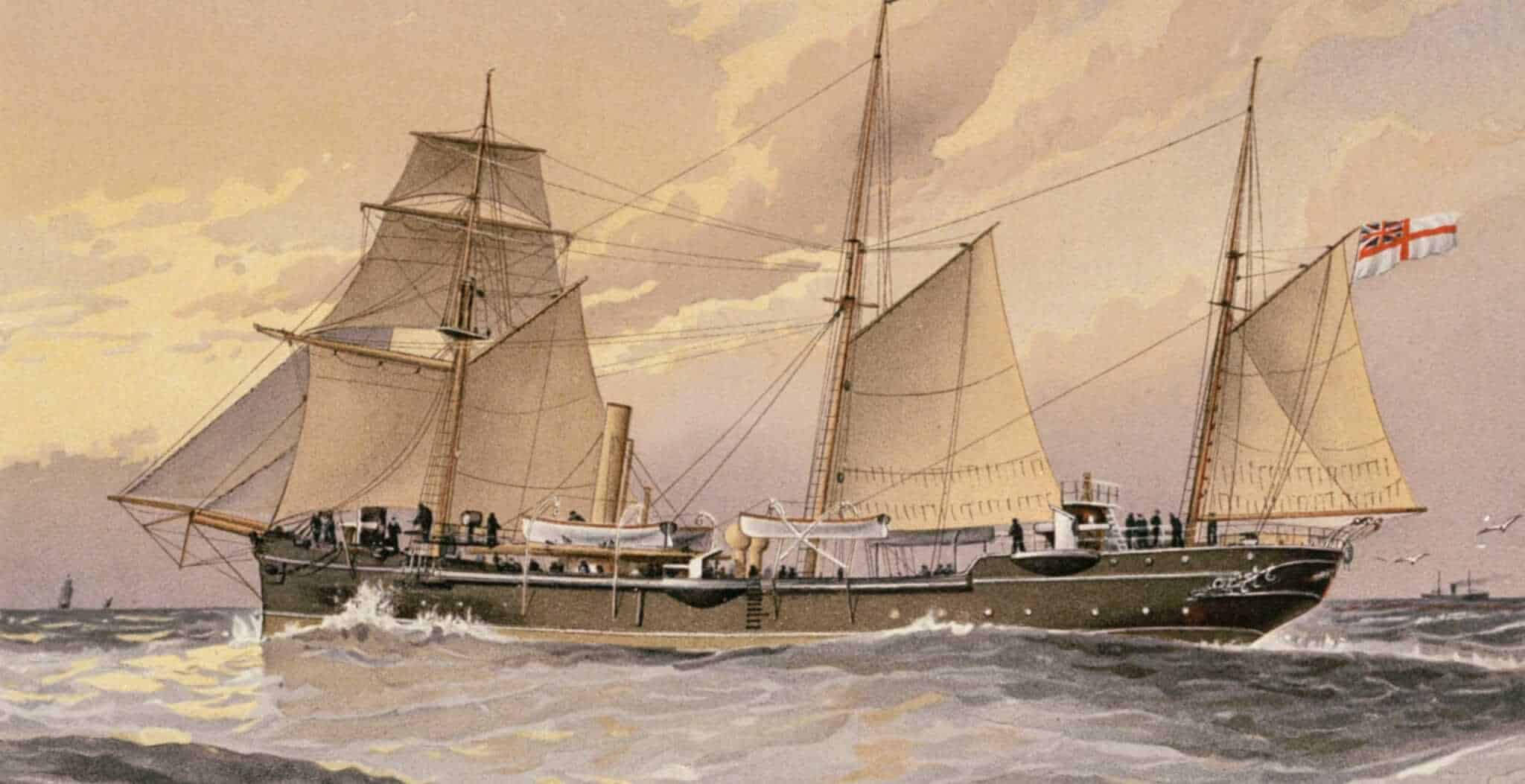

As Khalid dug in his heels, the British swiftly escalated their military presence in Zanzibar’s harbor. Rear Admiral Rawson, understanding the need for a decisive show of force, rapidly assembled his squadron. By the evening of August 25, the cruisers HMS Philomel and HMS Thrush, along with the gunboat HMS Racoon, were already positioned menacingly close to the Sultan’s palace. Rawson’s flagship, the powerful cruiser HMS St George, arrived on August 26, further bolstering British firepower. The small gunboat HMS Spitfire also joined the formation, rounding out the naval contingent. These vessels were equipped with modern naval artillery, including quick-firing guns, far superior to anything Khalid’s makeshift defenses could muster. Their strategic positioning allowed them to bring their formidable broadsides to bear directly on the palace and the Glasgow.

With his naval forces in place, Hardinge delivered a formal ultimatum to Khalid bin Barghash. The message was stark: Khalid was to evacuate the palace by 9:00 AM on August 27, 1896. Should he fail to comply, the British squadron would open fire. The ultimatum left no room for negotiation or further delay. It was a clear demonstration of British resolve and a demand for immediate capitulation.

During this tense standoff, Khalid desperately sought external support. He sent urgent pleas to the German consulate, hoping that Germany, as a rival colonial power, would intervene on his behalf. However, the German consul, while acknowledging Khalid’s predicament, was unwilling and unable to offer military assistance. The Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty had already settled the issue of Zanzibar’s status, and Germany had no desire to provoke a direct military confrontation with the mighty British Empire over a minor Sultanate. The German consul merely advised Khalid to comply with the British demands, offering him sanctuary at the German consulate should he decide to flee. This lack of intervention from Germany underscored the futility of Khalid’s defiance and the undeniable reality of British dominance.

Throughout the night of August 26 and into the early hours of August 27, the atmosphere in Zanzibar City was thick with tension. Khalid’s forces, estimated to be around 2,800 men—comprising palace guards, armed civilians, and a contingent of the Sultan’s personal retinue—worked frantically to reinforce their positions, piling up anything they could find as barricades. Despite their numbers, they were poorly trained, ill-equipped, and lacked the discipline and firepower to face a modern naval force. The British ships, meanwhile, prepared for battle, their guns loaded and crews at action stations, awaiting the precise moment of the ultimatum’s expiry. Observers from other European consulates and the local population watched with bated breath, knowing that dawn would bring either a peaceful resolution or a swift, brutal confrontation.

The Battle: 38 Minutes of Fury

As the tropical sun began to ascend on the morning of August 27, 1896, the clock ticked relentlessly towards 9:00 AM. The British squadron lay silent and menacing in the harbor, their guns trained on the Sultan’s palace. On shore, Khalid and his defiant loyalists braced themselves for the inevitable. At precisely 9:00 AM, with no sign of Khalid’s compliance, Rear Admiral Rawson gave the order. The flagship, HMS St George, fired the first shot, and the serene morning air was ripped apart by the thunderous roar of naval guns.

The British bombardment was immediate and devastating. The large-caliber shells from the cruisers and gunboats slammed into the palace complex with terrifying force. Walls crumbled, wooden structures splintered, and the makeshift barricades proved utterly ineffective against such firepower. The primary targets were the palace itself, the adjacent Harem, and crucially, the H.H.S. Glasgow, anchored in the harbor.

The Glasgow, Khalid’s only naval asset, mounted a brief but futile resistance. Its antiquated cannons fired a few rounds, but they were no match for the rapid-firing guns of the British squadron. Within minutes, HMS Thrush and HMS Racoon had reduced the Glasgow to a burning wreck. The Sultan’s yacht quickly sank, taking many of its crew with it.

On land, the scene was one of utter chaos and carnage. Khalid’s unfortified palace guards and armed civilians, caught in the relentless barrage, had no effective means of defense. Their rifles and a few outdated artillery pieces were useless against the armored British warships. The British shells ripped through the crowded palace grounds, causing massive casualties among Khalid’s loyalists. Estimates suggest that hundreds of Zanzibaris were killed or wounded in the brief bombardment, caught between the collapsing buildings and the overwhelming firepower.

The battle raged for a mere 38 minutes. The sheer intensity and destructive power of the British naval guns left Khalid’s forces no hope of resistance. By 9:38 AM, with the palace a smoking ruin, significant casualties, and the H.H.S. Glasgow sunk, a white flag was finally raised over the shattered remnants of the Sultan’s palace. The shortest war in recorded history had come to its swift and decisive end.

Aftermath and Consequences: Reshaping Zanzibar

The immediate aftermath of the Anglo-Zanzibar War was grim. British landing parties secured the ruined palace and its surroundings, while medical teams tended to the wounded. Miraculously, despite the heavy bombardment, British casualties amounted to only one wounded petty officer on HMS Thrush, who sustained injuries from a shell fragment. The disparity in casualties underscored the one-sided nature of the conflict. For the Zanzibaris, however, the cost was immense, with estimates ranging from 500 to 1,000 dead or wounded, a devastating toll for such a brief engagement.

In the chaos of the battle, Khalid bin Barghash managed to escape the burning palace. Along with approximately forty of his closest followers, he fled to the nearby German consulate, seeking asylum. The German authorities, adhering to international diplomatic conventions, granted him sanctuary, though they made it clear that they would not interfere with British political control over Zanzibar. Khalid remained under German protection at the consulate for several weeks, carefully monitored by the British.

With Khalid neutralized, the British swiftly moved to install their chosen successor. On August 27 itself, Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed, the pro-British candidate, was formally proclaimed the new Sultan of Zanzibar. His ascension cemented British control over the Sultanate and ensured a ruler who would cooperate fully with their agenda.

The Anglo-Zanzibar War served as an undeniable demonstration of British imperial power and a stark reminder of the realities of the “protectorate” system. Zanzibar’s nominal independence was now undeniably subservient to British authority. The incident underscored that any deviation from British directives, particularly regarding succession, would be met with overwhelming force.

One of the most significant long-term consequences of Hamoud’s installation was the acceleration of the anti-slavery movement in Zanzibar. Unlike his predecessors, Hamoud was committed to ending the slave trade, a key British objective. In 1897, largely under British pressure, he signed a decree formally abolishing slavery in Zanzibar, although the complete eradication of the practice took several more years due to deeply entrenched economic interests. This marked a major victory for British humanitarian efforts and solidified their moral justification for intervening in the region.

Khalid bin Barghash’s story did not end with his escape. He remained at the German consulate until October 2, 1896, when he was discreetly spirited away by the German Navy on the cruiser SMS Seeadler to Dar es Salaam in German East Africa. He lived in exile there for many years. His presence, however, remained a minor irritant for the British, who occasionally requested his extradition. His ultimate fate came during World War I when British forces invaded German East Africa. Khalid was captured by the British in 1916 and subsequently interned on Saint Helena and later on the Seychelles. He was finally allowed to return to East Africa in 1921, where he died in Mombasa, Kenya, in 1927.

Conclusion: A Microcosm of Imperial Might

The Anglo-Zanzibar War, though lasting a mere 38 minutes, encapsulates the raw power dynamics of the late 19th century’s “Scramble for Africa.” It was a swift, brutal, and utterly lopsided demonstration of British naval supremacy and imperial will. The conflict served as an unambiguous message to any local ruler who dared to defy the established colonial order: resistance was futile against the might of the British Empire.

More than just a historical curiosity, the shortest war in history stands as a potent symbol. It highlights how seemingly minor events, such as a succession crisis on a small island, could trigger overwhelming military responses when imperial interests were at stake. For Zanzibar, the war solidified its status as a British protectorate, paved the way for the effective abolition of the slave trade, and forever altered its trajectory within the British sphere of influence. It remains a fascinating, albeit sobering, reminder of an era when global power was concentrated in the hands of a few dominant empires, shaping destinies with swift and decisive force.