Vaša košarica je trenutno prazna!

The Siege of Jerusalem (1099): The Pivotal Climax of the First Crusade

In the scorching summer of 1099, after two and a half years of relentless marching and unimaginable hardships, the ragged and battle-hardened remnants of the First Crusade stood before their ultimate prize: Jerusalem. This was no mere city; it was the Holy City, the spiritual heart of their quest, and the very reason they had left their homes and spilled so much blood. The stage was set for a pivotal, yet deeply controversial, climax to a holy war that would forever alter the course of relations between East and West.

The Genesis of a Holy War: From Clermont to the Gates of the East

The spark that ignited the First Crusade came from Pope Urban II’s impassioned appeal at the Council of Clermont in November 1095. He painted a grim picture of Christian suffering in the East, calling for the liberation of Jerusalem and the Holy Sepulchre. His motivations were complex: a fervent desire for religious devotion and remission of sins, an aim to strengthen papal authority and unite Western Christendom, and the lure of material incentives like wealth and land for many landless knights and impoverished commoners.

The cry “Deus vult!” (God wills it!) swept across Europe. While an initial “People’s Crusade” ended in disaster, the more organized Princes’ Crusade, led by figures like Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond IV of Toulouse, and Bohemond of Taranto, pushed eastward. Their journey was a brutal crucible of starvation, disease, and constant skirmishes with the Seljuk Turks. Major sieges like Nicaea and, most notably, the eight-month ordeal at Antioch, tested their resolve to its limits. The supposed “discovery” of the Holy Lance at Antioch rekindled their flagging spirits, fueling a desperate victory that, though costly, solidified their burning desire for Jerusalem.

Glimpsing the Holy City: The Final Approach

Following the horrors of Antioch, the crusaders, though severely depleted, pressed on. The political landscape of the Levant inadvertently aided them: the Muslim world was fragmented, with the Seljuk Turks to the north and the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt controlling Jerusalem to the south. The Fatimids, initially underestimating the crusaders, soon realized their true intent.

The Fatimid governor of Jerusalem, Iftikhar ad-Dawla, prepared for the inevitable siege by reinforcing the city’s formidable walls, poisoning wells outside the city, and stripping the surrounding countryside. He even expelled many local Christians, fearing they might aid the besiegers – a decision that proved to be a strategic blunder.

On June 7, 1099, the crusader vanguard crested a hill, and before them lay the ancient, holy walls of Jerusalem. Chroniclers describe an indescribable emotional moment, with men weeping and kneeling. However, the spiritual triumph quickly gave way to stark reality: the city was a formidable fortress, and the crusader army, a mere shadow of its former self (estimated at 12,000-15,000 fighting men), faced a crippling lack of water in the parched landscape.

The Siege Commences: A Battle Against Walls, Thirst, and Despair

The immediate challenges were immense. Water scarcity led to terrible suffering and dwindling numbers. Crucially, the crusaders had arrived with virtually no proper siege equipment. Their initial uncoordinated assault on June 13 was a dismal failure. Despair loomed once more.

However, faith and fortune intervened. A vision prompted a barefoot procession around the city walls on July 8, mimicking the biblical siege of Jericho. This act of profound religious devotion powerfully boosted morale and instilled fear in some defenders. At almost the same time, news arrived that Genoese and English ships, laden with vital supplies, timber, tools, and skilled engineers, had landed at Jaffa. This was the pivotal turning point.

The crusaders immediately began the arduous task of constructing massive siege towers, battering rams, and catapults. Ships were painstakingly dismantled, their timbers hauled inland. Under the blazing sun, two colossal siege towers were built: one for Godfrey of Bouillon targeting the northern wall, and another for Raymond of Saint-Gilles on the southern wall. These towering structures were their only hope.

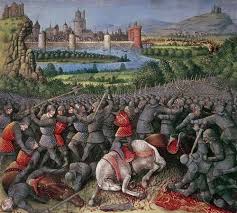

The Final Assault: Blood on the Holy City (July 13-15, 1099)

With the siege engines complete, the final, decisive assault began on July 13. Raymond of Saint-Gilles launched a major diversionary attack on the southern wall, drawing the bulk of the defenders’ attention. The true tactical genius lay in Godfrey of Bouillon’s strategic shift: under cover of darkness on the night of July 13-14, his massive siege tower was secretly disassembled and painstakingly reconstructed on the weaker northeastern section of the wall, near the present-day Gate of Herod.

This audacious maneuver completely surprised the Fatimid garrison when dawn broke on July 15. Godfrey’s towering engine lumbered forward, and despite fierce resistance, crusader engineers extended a bridge onto the wall. The first crusaders, including a knight named Lethold, breached the defenses, opening the floodgates. Crusaders poured into the city through the northern wall, overwhelming the outflanked defenders. Simultaneously, Raymond’s forces also breached the southern wall.

What followed was one of the most horrific massacres in the history of warfare. The crusaders, fueled by years of pent-up rage, religious fanaticism, and profound hardship, unleashed unimaginable fury. Muslims, Jews, and even some local Eastern Christians caught in the crossfire were indiscriminately slaughtered. Chroniclers, both Christian and Muslim, paint a grim picture: “men rode in blood up to their knees and even to the bridles of their horses,” as reported by Raymond of Aguilers. The most infamous atrocity occurred within the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, where countless refugees were massacred. Estimates of the dead vary wildly, but the scale of the carnage was immense and indiscriminate.

The brutality stemmed from a complex mix of religious fanaticism, trauma and a desire for revenge, the promise of plunder, a breakdown of discipline, and the dehumanization of the enemy as “infidels.” In a disturbing paradox, just hours after the wholesale slaughter, the crusaders, many still covered in blood and laden with spoils, made their way barefoot to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, their holiest shrine, to give thanks for their “victory.”

Aftermath and the Birth of a Precarious Kingdom

With Jerusalem taken and “cleansed,” the crusader leaders faced the challenge of governance. Raymond of Saint-Gilles famously refused the crown. Instead, Godfrey of Bouillon was elected “Advocate of the Holy Sepulchre,” refusing the title of King out of reverence. He died in July 1100 and was succeeded by his brother, Baldwin I, who became the first actual King of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.

This marked the formal establishment of a new political entity in the Levant, an alien Frankish kingdom surrounded by a vastly larger and increasingly hostile Muslim population. Its survival depended on continuous fresh waves of crusaders from Europe, crucial naval support from Italian city-states, and the establishment of powerful military orders like the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller. The crusader states also survived by exploiting the existing Muslim disunity.

The immediate repercussions of the siege rippled across the Muslim world, sparking shock and outrage. While no immediate unified counter-crusade materialized due to internal fragmentation, the fall of Jerusalem was a profound blow to Islamic pride. This event slowly began to galvanize calls for Jihad, a concept that would be powerfully re-energized by charismatic leaders like Zengi and, later, Saladin, in the decades that followed.

Enduring Legacy: A Scar on History and a Contested Memory

The Siege of Jerusalem in 1099 stands as a monumental event, a stark dividing line in the history of the Mediterranean and the Middle East. For Latin Christendom, it was an unprecedented triumph, the audacious fulfillment of a spiritual vow. For the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants of Jerusalem, it was a devastating catastrophe marked by unspeakable brutality and the imposition of foreign rule.

Its legacy is complex, deeply contested, and enduring. It cemented a narrative of conflict and mistrust between East and West that has echoed through the centuries, influencing diplomatic relations, cultural perceptions, and historical narratives even today. In Western historical memory, it often represents a heroic chapter of faith and perseverance. However, in the Middle East, the memory of the Crusades, and especially the fall of Jerusalem, remains a powerful and often painful symbol of foreign invasion and historical grievance. This differing interpretation highlights how history is a complex interplay of perspectives.

The events of July 1099 were not merely a battle; they were a cataclysm that profoundly shaped the future. They initiated nearly two centuries of Crusader presence in the Levant, fostering a hardening of religious lines and fueling mutual suspicion and animosity that would reverberate for centuries.

The Siege of Jerusalem remains a testament to both extraordinary human determination and horrific brutality. It was the culmination of an epic spiritual quest that ended in a massacre, creating a paradox of faith and violence that continues to challenge understanding. It was a violent new beginning for the intricate relationship between Europe and the Middle East, a moment forever etched in the annals of history.