Vaša košarica je trenutno prazna!

For centuries, Western history books have celebrated the likes of Columbus, Magellan, and Da Gama as the pioneering figures who “discovered” the world. Yet, a compelling question lingers: Did China, with its sophisticated maritime technology and vast resources, reach distant lands long before European explorers ever set sail? The incredible voyages of Admiral Zheng He offer a powerful, often overlooked, counter-narrative to this Eurocentric view of global exploration, challenging what many believed to be settled history.

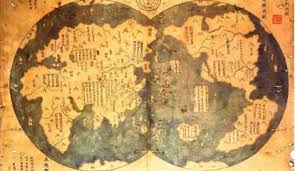

The myth of European exclusivity in global exploration begins to unravel when we delve into the Ming Dynasty’s golden age of maritime power. From 1405 to 1433, a staggering seven expeditions were launched under the command of the formidable eunuch admiral, Zheng He. These weren’t mere reconnaissance missions; they were epic demonstrations of imperial might and advanced engineering. Imagine fleets of colossal “treasure ships”—some reportedly five times the size of Columbus’s Santa María—carrying thousands of sailors, soldiers, and scholars, stretching for miles across the open sea. This scale of naval power was utterly unprecedented and remained unmatched for centuries.

Zheng He’s primary objectives were diplomatic, commercial, and demonstrative. His fleets sailed far beyond the familiar waters of the South China Sea, navigating the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean, reaching the Arabian Peninsula, and, crucially, making repeated landings along the coast of East Africa. Historical records, archaeological evidence, and even local legends from places like modern-day Kenya and Somalia confirm direct contact between Chinese mariners and African kingdoms. These encounters weren’t about conquest, but about establishing trade relationships, exchanging valuable goods, and collecting exotic animals for the imperial menagerie, including giraffes, which captivated the Chinese court.

The technological prowess behind these voyages was nothing short of revolutionary. Chinese mariners utilized sophisticated magnetic compasses, detailed star charts, and precise astronomical observations for navigation. Their shipbuilding techniques were centuries ahead of their time, featuring innovations like watertight compartments that made their massive ships remarkably resilient to storms—a design element only adopted by European shipbuilders much later. This mastery of the seas allowed Zheng He’s fleets to traverse immense distances with an astonishing degree of accuracy and safety.

The stark contrast between China’s early global reach and its subsequent withdrawal from maritime exploration presents a fascinating historical “what if.” After Zheng He’s final voyage and the death of his imperial patron, the Yongle Emperor, a dramatic shift in imperial policy occurred. The vast fleets were dismantled, the valuable navigational charts and records were largely neglected or even destroyed, and China turned inward, prioritizing land-based defense and internal stability. This momentous decision left a vacuum that European powers would later fill, embarking on their own age of discovery.

Zheng He’s voyages force us to reconsider the established narratives of world history. They reveal a period where China was undeniably the dominant naval power, capable of connecting continents and cultures long before the names of European explorers became synonymous with global circumnavigation. By shedding light on this forgotten chapter, we gain a richer, more nuanced understanding of humanity’s shared journey of exploration and interconnectedness, prompting us to ask: What other historical “discoveries” might be waiting to be re-evaluated?